News — 13 December, 2018

Digitising Kathmandu from above

Guest blog by Gaurav Thapa from Kathmandu Living Labs. Covering the digitisation process carried out by the team for mapping building footprints in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal as part of the METEOR project.

This blog outlines the mapping carried out by KLL as part of the HOT METEOR project. Please check out the dedicated OSM wiki page for more details project.

Project

Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL) is working together with the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) on the Modelling Exposure through Earth Observation Routines (METEOR) project. Our work is part of a larger collaboration between HOT, the British Geological Survey, ImageCat, and the UK Space Agency International Partnership Programme. This overall project is focused on developing innovative applications of earth observation (EO) technologies to improve understanding of exposure to help minimise risks from natural hazards. We are working directly with HOT on the digitization and the subsequent building exposure survey of Kathmandu Valley.

State of the Map: Kathmandu Valley

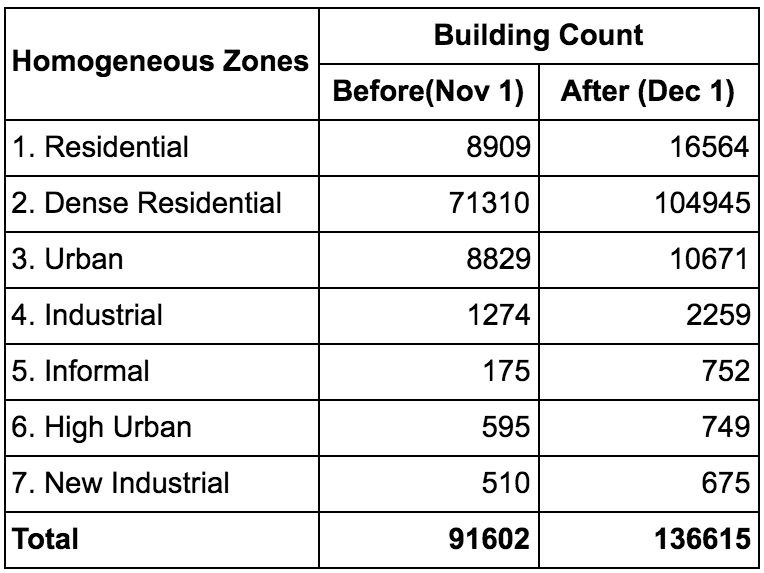

For this project urban areas of Kathmandu Valley were divided into 7 homogeneous zones. These homogeneous zones were created based on ImageCat’s model where they took remotely sensed imagery to find similar development patterns and based on that seven zones were identified for mapping.

At the start of the project, the aggregate area of the homogeneous zones chosen for mapping had a total of 91,602 buildings mapped on OSM. Most of these buildings had been built right after the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake. During this time new imagery had been made available for mappers and a fairly thorough job of mapping had taken place. Mapping activities which had taken place after this time period were done by mappers using the free Bing and Mapbox imagery. However, the poor resolution of the free imageries (both in terms of temporal and spatial) and the lack of clear outputs in the subsequent mapping efforts meant that the map of Kathmandu had not been properly updated in four years.

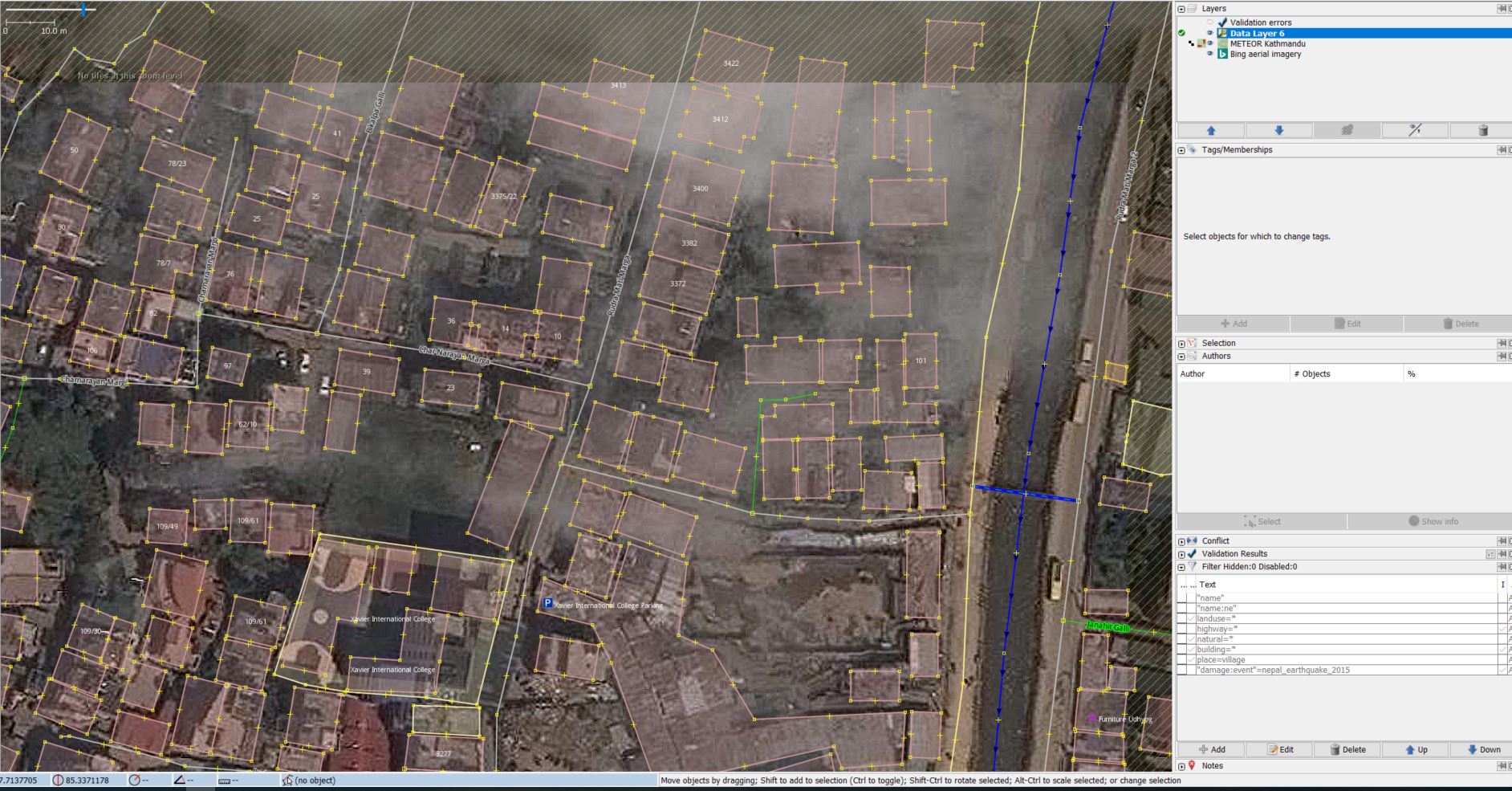

In the below image, a randomly selected building is found to have been created and last modified on 30 April 2015. You can also see that the buildings are not easily distinguishable through the currently available satellite imagery leading to significant underdigitization of buildings or aggregation of buildings. Buildings have also not been orthogonolized, and there is significant offset between the OSM data and the satellite imagery.

Image 1: Initial data with new satellite imagery

Image 1: Initial data with new satellite imagery

How we approached remotely mapping such a complex area?

From the above example, we know that the biggest challenge stems from not having an updated high resolution satellite imagery. In order to do this, our friends at USAID’s GeoCenter, a part of the U.S. Global Development Lab’s Center for Digital Development helped us by processing and creating a Tiled Map Service of the new mosaicked satellite imagery. This new imagery was integral for us to add most of the buildings that had been built in the last four years. The new imagery also had better resolution and sharper contrast. This allowed us to distinguish buildings built adjacent to each other. Overall, the new imagery allowed us to add and modify a further 45,013 (still increasing as members of OSM community volunteer our time to improve Kathmandu) buildings.

Almost 19,000 of these buildings were modifications that were carried out during the project period. Though modifying buildings take a lot longer than tracing new buildings, it allows us to retain OSM history which is considered vital in the OSM community. Two images below show the difference in data.

Image 2: Homogenous Zone 1- Bhaktapur with previous data overlayed on Bing imagery

Image 2: Homogenous Zone 1- Bhaktapur with previous data overlayed on Bing imagery

Image 3: Homogenous Zone 1- Bhaktapur with latest data overlayed on New imagery

Image 3: Homogenous Zone 1- Bhaktapur with latest data overlayed on New imagery

One of the challenges of working with OSM in Nepal is that there are many people from outside the country who want to help map Kathmandu due to the surge in need of mapping post-Earthquake. Unfortunately, this leads to a lot of beginner mappers ‘learning by doing’ in Kathmandu. The density of the buildings makes this very challenging which can lead to scenarios where mappers create overlapping buildings using multiple image sources.

Image 4: Error ridden section of Kathmandu

Image 4: Error ridden section of Kathmandu

Correcting such errors and aligning the new imagery, bing imagery and data layers took a significant amount of time.

Image 5: Errors corrected

Image 5: Errors corrected

As image 5 shows, even the latest satellite imagery had sections where tracing building was not possible. This was because the contrast was not good most likely due to dust cover. Unfortunately, the poor satellite imagery covered the urban core of Kathmandu and were areas that are highly dense. These were labeled as poor imagery and only clearly visible building were traced in these areas. We hope to improve this data while on the ground.

Timeframe

We wanted to complete the remote mapping portion of the project before the beginning of December. In order to do this, we recruited 8 students from Pokhara. The students worked for weeks with our expert mappers to digitize an additional number of around 45,000 buildings.

Images 6 & 7: Remote mappers

Images 6 & 7: Remote mappers

Result and way forward

We reiterate that the result of the project was an addition of 45,013 buildings. The table below shows the breakdown of this number in terms of specific homogeneous zones created by ImageCat.

However, the mapping effort was not limited to buildings. Nor was it limited to the core area. This was because one of the biggest challenges of mapping in Kathmandu was modifying and updating the existing OSM data. This meant that at times mappers would have to go beyond the designated areas to modify and align the data. If you look at the data from missing maps (image 8 below) you will find that over 70,000 buildings were modified or created and over 96 km of roads were traced.

Image 8: Statistics from missing maps

Image 8: Statistics from missing maps

These stats also show that periodic concentrated efforts of mapping is vital for countries like Nepal where the OSM community is not as robust as in Europe or the Americas. The amount of error correction that had to be done also tells us that (i) even remote mapping should be led locally and (ii) adequate focus must be given to periodic updating, gardening, and cleaning of data in order to best utilize the OSM data that has been generated.

For the project, we will continue to work with HOT for the next three months to field validate and add building attributes to as many as 3,000 of these traced buildings.